Up to now, the incompetent measures of the Duterte regime in resolving the pandemic crisis haunt the peasant and rural-based sectors. Farmers, peasant women, agricultural workers, fisherfolk, and indigenous peoples suffer from the impact of the lockdown due to loss of livelihood, bankruptcy, penniless, and distraught. To date, calling for support and production subsidy persists as many families are unable to make a living such as farmwork due to the pandemic thus, hunger and poverty are present. However, the Duterte regime adopts militaristic measures under the guise of response to the public health and economic crisis being faced by the Filipino people.

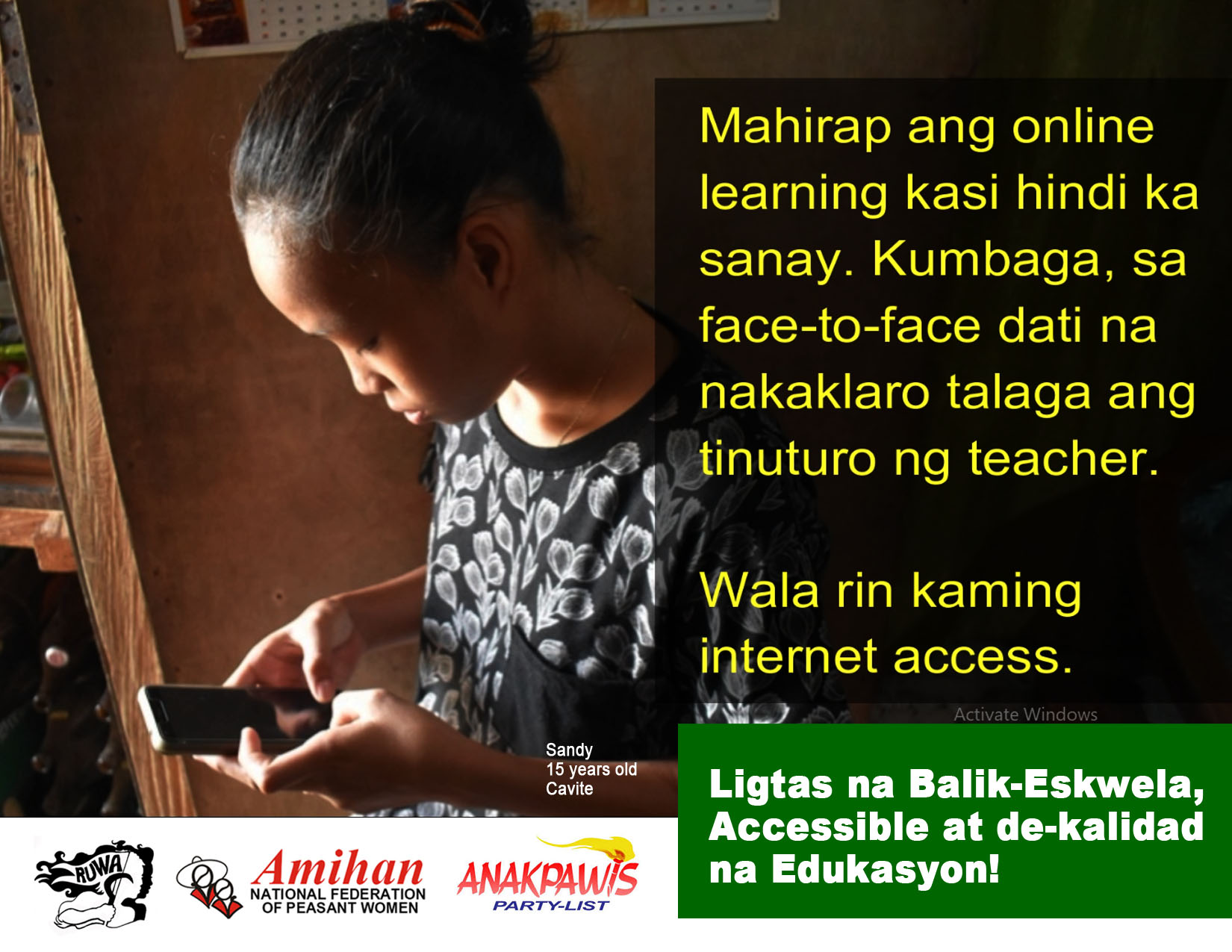

Amid end of pandemic still not in sight, the Department of Education announces that instead of face-to-face, alternative learning modalities will be used when classes start in October 5, 2020. They encourage the parents to choose from the following alternative modes of learning such as online and modular. DepEd’s proposal was met with criticisms from the teachers, poor parents and students in the urban and rural communities and various people’s organizations. This recent months, social media and news outlets exposed photos of teachers from various provinces looking for internet signals to attend webinars, submit some documents online and difficulties in preparing for modules without a government support.

In rural areas, the National Federation of Peasant Women exclaims that the distance learning was discriminatory and incompatible to poor peasant families in the provinces and will put peasant youth-students into disadvantaged positions once classes resume on October 5. Likewise, it will compromise the accessibility and quality of education. Before the opening of classes, Amihan with Rural Women Advocates and Pamalakaya gathered community-based data on the preparedness and the possible impact of distance learning on the peasant families and children in Bacoor, Cavite and Rodriguez, Rizal.

The first casualty of online enrollment

Last June 16, 2020, Baretang Bikolnon, a media outlet in Bicol, reported a 19-year old male junior high school student who died by suicide from Brgy. Fidel Surtida, Sto. Domingo town, Albay due to worries of high costs of enrollment. His mother said that the victim worried a lot about the cost of buying load and exorbitant internet charges for his online enrollment.

Peasant organizations stated then that the suicide was induced by the policies of the Duterte government such as the burden of distance learning to the peasant families. But the Deped said that the statement was ” irresponsible and malicious, as it does not respect the deceased and the orphaned family. It is misleading the public on the true plan of the DepEd for the coming school year.” Its response is misleading itself, as it was the victim’s family who revealed what led to the suicide. It was distance learning itself.

The DepEd even attempts to carry out mass deception by claiming it is not blind to the reality and learned of the uneven situation of students and communities. But this early, its proposal is already causing misery to poor families, particularly from the countryside. A mother of four in Cavite was forced to borrow money to buy a cellphone for online enrollment as well as a mother in Rodriguez even though their place has no signal and relied solely on solar power.

Doubts on modular learning

Peasant families have opposed online learning obviously due to low household incomes and they prioritize buying food and other necessities. Buying gadgets, laptops and alloting for internet loads as requirements for online learning is out their options. Their geolocation adds to the impossibility as internet signal is absent and power interruptions are recurring. Even those already owning cheap smartphones claim they are not capable of video calls for long periods.

Thus, poor peasant families who intend to continue the education of their children are left with the option of modular learning. But peasant women doubt its effectiveness, accessibility and learning quality. Mothers are not confident in tutoring their children clearly due to their low educational attainment. Most only reached elementary and high school levels, and are not familiar with the lessons adopted by the DepEd. Moreover, they are preoccupied with work on farms, livelihood and household chores. Their daily ultimate goal is to secure food for the next meals.

In Rodriguez town in Rizal province, many peasant women worked in farms and quarrying sites while in Bacoor City, Cavite, they either fish or help their husbands in their fishing activities, carrying out ancillary tasks. A peasant mother from Rodriguez who prefers modular learning is now anxious of the school’s chosen mode as her child is a beneficiary of the voucher program. Amid claims that modular mode does not require peripherals or gadgets, some of the teachers require the parents to have access to e-mail or group chats intended for distributing copies of the exams. The peasant women also worry of their lack of knowledge on the questions on the module, thus, they will be forced to buy loads to communicate with teachers or for research in the internet. They claim, if this mode becomes unsustainable, their children may be forced to stop schooling.

Moreover, single parents in the rural areas are either firm not to or undecided to enroll their children this coming school year. They cite economic incapacity to any of the modes of learning. Some parents enrolled their children but are still undecided on the mode. They also consider their children to stop schooling as an option. Nobody chose the tv/radio-based learning mainly because of not having them and are not fully informed on the its mechanics.

Postponement of classes

Many peasant women suggested the postponement of the opening of classes, until the pandemic and economic crises are resolved. Majority of them prefer face-to-face classes. They stressed that they are preoccupied with making a living and are still recovering from the loss of incomes brought about by the lockdown. They are calling for government assistances such as financial, livelihood and production subsidy.

Lastly, the testimonies of peasant women expose anxiety and the possibility of many children having to stop schooling. They doubt the effectiveness, accessibility and quality of the DepEd’s proposed distance learning. Amid their bases, mainly due to deteriorating household incomes, location and lack of infrastructure, low educational attainment and generally their low standard of living, the distance learning appears inappropriate for the poor peasant families. Thus, as conclusion if peasant families are prepared for this, they are obviously not, and the DepEd should reconsider their plans, with the situation and welfare of the most marginalized sectors in the country as benchmark and not those from privileged upper classes in the urban centers, to which internet access, purchasing of gadgets and other pheripherals are already part of their daily lives. ###