As the COVID-19 pandemic was belittled in the past months, President Rodrigo Duterte, with his minions at the Inter-Agency Task Force on Emerging Infectious Diseases (IATF-EID) responded with a martial law-like lockdown, packaged as an enhanced community quarantine (ECQ) of the Luzon major island, last March 16 to originally April 12, but extended to April 30, and followed by the extension for Metro Manila, Calabarzon and Central Luzon regions until May 15. It was a military solution, and not a medical response, and was characterized by countless checkpoints, military and police deployment in communities subjected akin to hamletting, that even the entry of food are questioned, relief efforts are barred, on top of the broad people already thrown into mass unemployment, hunger and rights abuses.

The Filipino people demanded legitimate measures as response to the public health emergency, but the Duterte regime pursued its criminal neglect and intensified its militaristic approaches. The people demanded: (1) free mass testing, including the mass distribution of vitamins, hygiene and protective kits, mass disinfection measures and sanitation, as well as public information drives in communities; (2) employment and deployment of health worker frontliners to public hospitals and communities, and guarantee of their protection; (3) strengthening of the public health sector with increased budget allocation to fund free medical services to poor and most vulnerable sectors; (5) full utilization of the P275 billion emergency fund, and rechanneling the P4.5 billion presidential discretionary and intelligence fund, for medical response and social amelioration; (6) ensuring of accessibility and affordability of basic commodities and services, especially food items; (7) and provision of cash and food aid to basic poor sectors, and production financial assistance to peasants and other rural-based sectors.

In the rural areas, “food security frontliners” such as the farmers, peasant women, fisherfolk, indigenous people and agricultural workers suffered significantly as they remain marginalized or excluded from government and non-government relief efforts. Though the Department of Agriculture issued its token policy of exempting them from the lockdown, they were barred from fully attending their farms for full production, vending their produce at other barangays, and their input suppliers are barred to enter their farms, and finally they are unable to haul their produce to the town market as mass transport was cut-off.

According to Amihan Bikol, farmers and peasant women decried the continuing decline of farm gate prices of agricultural products which is an added burden to their miseries. Copra is at low P20 to P24 per kilo, while in Catanduanes, bandala abaca fell from its usual P91 to P101 per kilo to P70 per kilo.

Likewise, Amihan Isabela, as farmworker families were barred from entering other barangays, they lost potential income of around P5,000 for a three-week farm work. This is on top of the imposed curfew that limited their work on near farms. Poor farmers also lost their potential income of around P250 to P350 from selling agricultural products and odd-jobbings due to the lockdown.

In Nueva Ecija, rice farmers raised the alarm against the decrease in farm gate prices of palay, that fell by P0.50 per kilo, from P18 to P17.50 per kilo. Likewise, the farmgate prices of palay ranges from P12 to 19 per kilo – P12-14 in Bikol, P16 to 18 per kilo in Cagayan province and P19 per kilo in Isabela and Bataan provinces.

Moreover, rice farmers demanded the National Food Authority’s (NFA) massive procurement of local palay at least P20 per kilo farm gate price and pushed for the intensified relief distribution of rice stocks of the NFA rice to poor sectors affected by the lockdown. On the other hand, the Republic Act 11203 Rice Liberalization Law has shown its total failure during this pandemic as the government continues to rely on imported rice from Vietnam even though it has already announced its suspension of exports. The Department of Agriculture said that a total of 300,000 metric tons will arrive in the country during the lockdown.

Duterte’s lockdown is a de facto measure to throw farmers and peasant women into abrupt and worsened hunger, which eventually will generate its full impact on poor consumers in the urban centers who will suffer scarcity of food. The prices of commercial rice in the market increased from pre-lockdown month of February to the first week of April. Data from the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA) showed that prices of regular milled rice rose by P3.62 or 10% from P36.16 to P39.78 per kilo. At the Mega Q-mart public market in Quezon City, prices of regular rice were already at P40 per kilo.

Peasant women and their families decry lockdown’s impact, need urgent aid

The peasant women suffered fear and anxiety as they were unable to provide food for their families or they may run out of food, while being threatened by the checkpoints manned by elements of the police and military. The loss of their livelihood caused their non-capacity to buy food, medicines and other necessities. Some survived with their remaining vegetable crops, but it remained inadequate as the lockdown was extended. Some were also dismayed of slow growth of their vegetable crops due to absence of rainwater. A peasant family in Batangas survived by only eating once a day or lunch to save food, and in Rodriguez town, Rizal, they resorted to sweet potatoes, cardava bananas (saba) and other vegetables. More rampant, many families with children were anxious and unable to provide them milk, and maintenance medicines to the elderly. To cope up, they fell desperate victims to usury or loans with exploitative interest rates.

Based on Amihan’s research, the peasant families’ monthly cost of living reaches around P15,000 to P21,000. In Cagayan, Isabela, Rizal and Cavite provinces, the daily cost of living of peasant and fisherfolk families during this lockdown ranges from P478 to P700, which commonly includes 2 kilos of rice, fish, vegetables, condiments, coffee, sugar excluding the costs for allowance for schooling children, medicines and other needs.

Peasant women and their families were desperately appealing for financial assistance and food relief from the government but were provided with relief packs consumable for only two to three days. In Bataan, peasant families received a pack containing 3 kilos of rice, 3 sardines at 1 payless; in Isabela, they received a 7 kilos of rice, 5 sardines, ½ pancit miki, 50 grams of coffee and ½ kg of sugar for two consecutive relief distributions and in Cagayan, 7 kilos of rice and 3 sardines, 5 packs of payless.

Likewise, peasant women decried the discriminatory guidelines of the Social Amelioration Program (SAP) of the Department of Social Work and Development (DSWD). Many legitimate and poor farmers and peasant women were disqualified to receive P5,000 to P8,000 financial aid. In Isabela, the DSWD implemented a quota for the number of beneficiaries, of 40-50% of poor and marginalized sectors in the province based on their 2015 census. For example in the municipality of Cordon, only 7,522 families or 54% of the 13, 953 were given assistance under SAP. According to Asosasyon Dagiti Mannalon a Babbai ti Isabela (AMBI), Amihan’s provincial chapter in Isabela, the DSWD disqualified the following (1) farmworker families who earn as low as P250 per day; (2) farmers who have 1 hectare; families renting at other families’ residence; (3) bedspacing workers; (4) with houses of concrete materials; (5) those who have no IDs for solo parents, senior citizen, PWD and others; (6) minors already with own families; (7) with family members abroad who are unable to remit; (8) senior citizens waiting for pensions for the next month and (9) indigenous peoples in Sindon Bayabo, Ilagan town.

As alleviation to the lockdown’s impact, Amihan and its local chapters are calling for the distribution of P10,000 cash aid and the production subsidy of P15,000 to peasants, fisherfolks, agricultural workers and other rural-based sectors, in order to provide food on their tables and for food production to continue in the major island and whole country.

The role of peasant women organizations amid lockdown

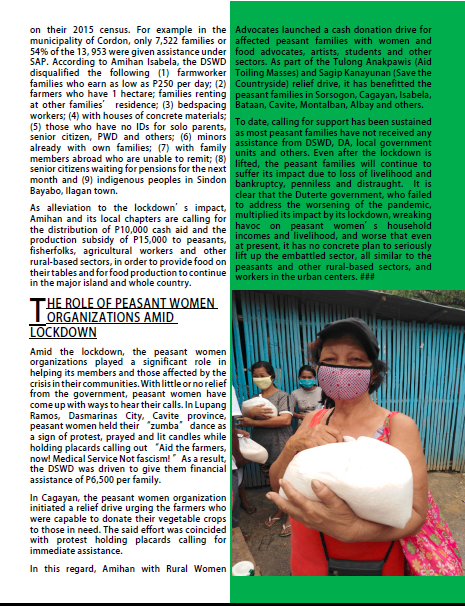

Amid the lockdown, the peasant women organizations played a significant role in helping its members and those affected by the crisis in their communities. With little or no relief from the government, peasant women have come up with ways to hear their calls. In Lupang Ramos, Dasmariňas City, Cavite province, peasant women held their “zumba” dance as a sign of protest, prayed and lit candles while holding placards calling out “Aid the farmers, now! Medical Service Not fascism! ”As a result, the DSWD was driven to give them financial assistance of P6,500 per family.

In Cagayan, the peasant women organization initiated a relief drive urging the farmers who were capable to donate their vegetable crops to those in need. The said effort was coincided with protest holding placards calling for immediate assistance.

In this regard, Amihan with Rural Women Advocates launched a cash donation drive for affected peasant families with women and food advocates, artists, students and other sectors. As part of the Tulong Anakpawis (Aid Toiling Masses) and Sagip Kanayunan (Save the Countryside) relief drive, it has benefitted the peasant families in Sorsogon, Cagayan, Isabela, Bataan, Cavite, Montalban, Albay and others.

To date, calling for support has been sustained as most peasant families have not received any assistance from DSWD, DA, local government units and others. Even after the lockdown is lifted, the peasant families will continue to suffer its impact due to loss of livelihood and bankruptcy, penniless and distraught. It is clear that the Duterte government, who failed to address the worsening of the pandemic, multiplied its impact by its lockdown, wreaking havoc on peasant women’s household incomes and livelihood, and worse that even at present, it has no concrete plan to seriously lift up the embattled sector, all similar to the peasants and other rural-based sectors, and workers in the urban centers. ###

Please check this link to download. https://drive.google.com/open?id=1Ea0JmIHJzvBIYbhdxTmTfRKNyQ3k0lz_