Stories of peasant women in Isabela province, Philippines

Introduction

In the Philippine countryside, “food security frontliners” or food-producing sectors such as the farmers, peasant women, fisherfolk, indigenous people, and agricultural workers suffered significantly from the abrupt and worsened hunger and poverty, which were consequences of the government’s militarist policies under a facade of response to the COVID-19 pandemic. A major component of this is the lockdown or labeled as community quarantine. This has exacerbated the more structural impact of liberalization policies in agriculture, recurring drought, successive typhoons, that manifests on lowered household incomes and even indebtedness.

Local lockdowns and road blockades took their toll as the food crisis or the recent price shocks in food and agricultural products. The obvious causes were lowered productivity as farmers were barred into working into other lands, local glut as travel of buyers were barred, an explosion in logistical costs due to increased travel time, and the gross failure of the government to effectively address the African Swine Flu epidemic that hounded the livestock sector. At the bitter end, the pandemic crisis on the top of agriculture’s chronic characteristics has worsened the state of peasant families’ household incomes vis-à-vis to their purchasing power, scarcity of food leading to mass hunger, the ruin of their susceptible houses, amid systematic marginalization, government neglect, and even abuses. Even after a year, the peasant sector has yet to fully recovered from the losses and debts they incurred since last year. It is a major driver for the sector to seriously demand immediate social amelioration and production subsidy from the government.

Testimonies of farmers and peasant women from their miserable experience during the Luzon-wide lockdown or the March to June “Enhanced Community Quarantine” (ECQ) highlighted the militarist barring of farmwork in other barangays (villages). Mass transport was also prohibited, narrowing the market for their harvest, throwing them into victims of underpricing. Mass anxiety has clouded the peasant women who usually sought food for their families, particularly their children. This is amid that they are constantly threatened at checkpoints manned by armed elements of the police and the military. The loss of their livelihood literally meant their incapacity to buy food, medicines, and other basic and prime commodities.

Moreover, some survived with their remaining vegetable crops, but they remained inadequate as the lockdown was extended. Some were also dismayed by the slow growth of their vegetable crops due to the absence of rainwater. Many peasant families survived by only eating once a day at lunch to save stocks, and others resorted to sweet potatoes, “saba” (cardava bananas), vegetables, and root crops. More rampant was that many families with children were anxious and unable to provide the milk and maintenance medicines to the elderly. To cope up, they endured being victims of usury or loans with exploitative interest rates.

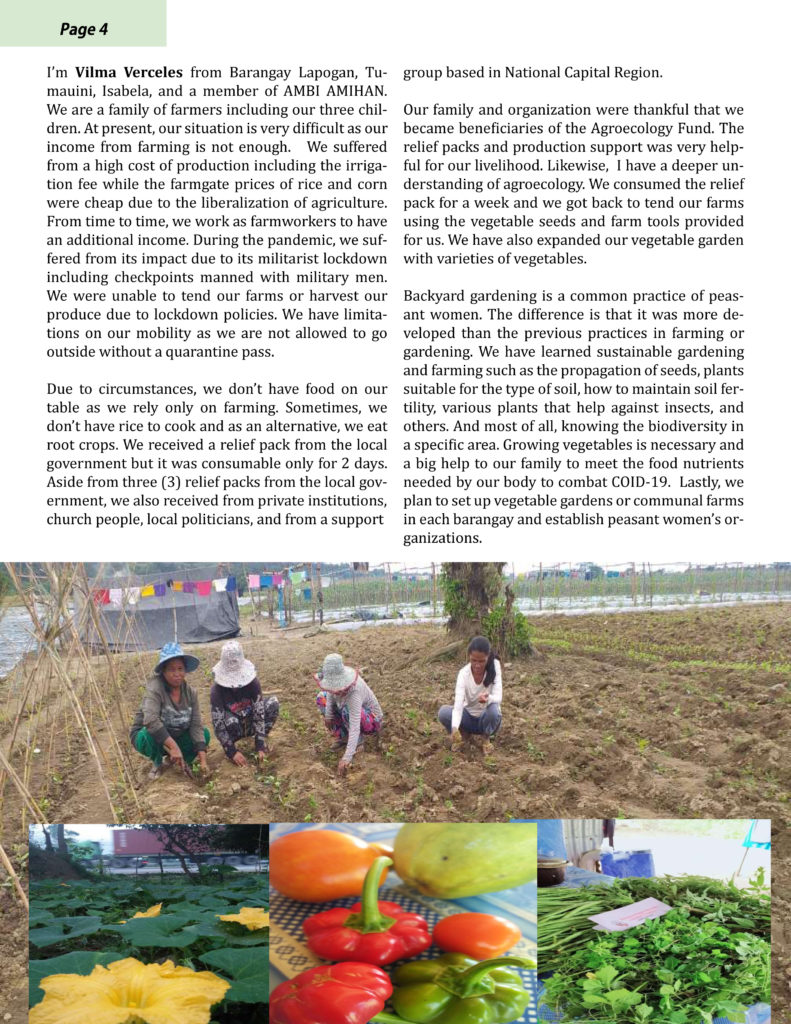

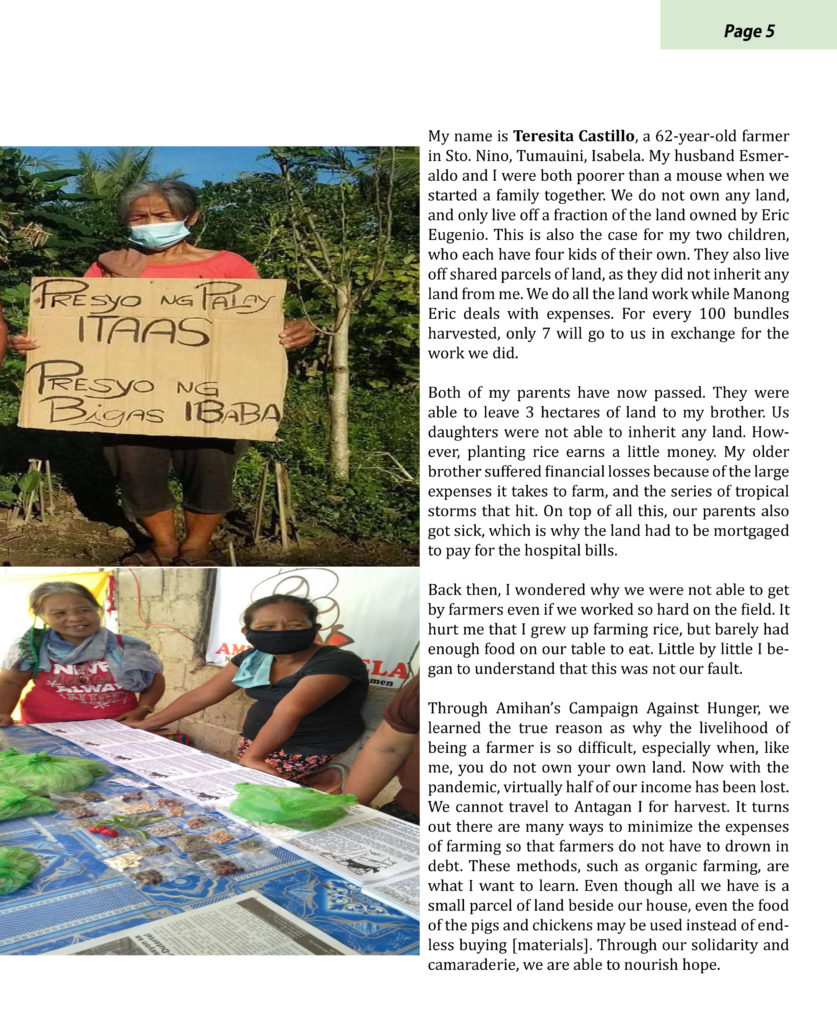

As they anticipate the worsening crisis, the peasant women, fortunately at their relatively high level of organization, took the noble aim of carrying out mass campaigns to demand food relief, social amelioration, and broaden their linkages to other sectors for aid. They initiated their own relief drive efforts urging farmers who have a surplus harvest to donate to those others in need. The mass actions or local protests they carried out such as posting on social media of photos with them holding placards written with legitimate demands earned them further support from other sectors in the locality and in the national center.

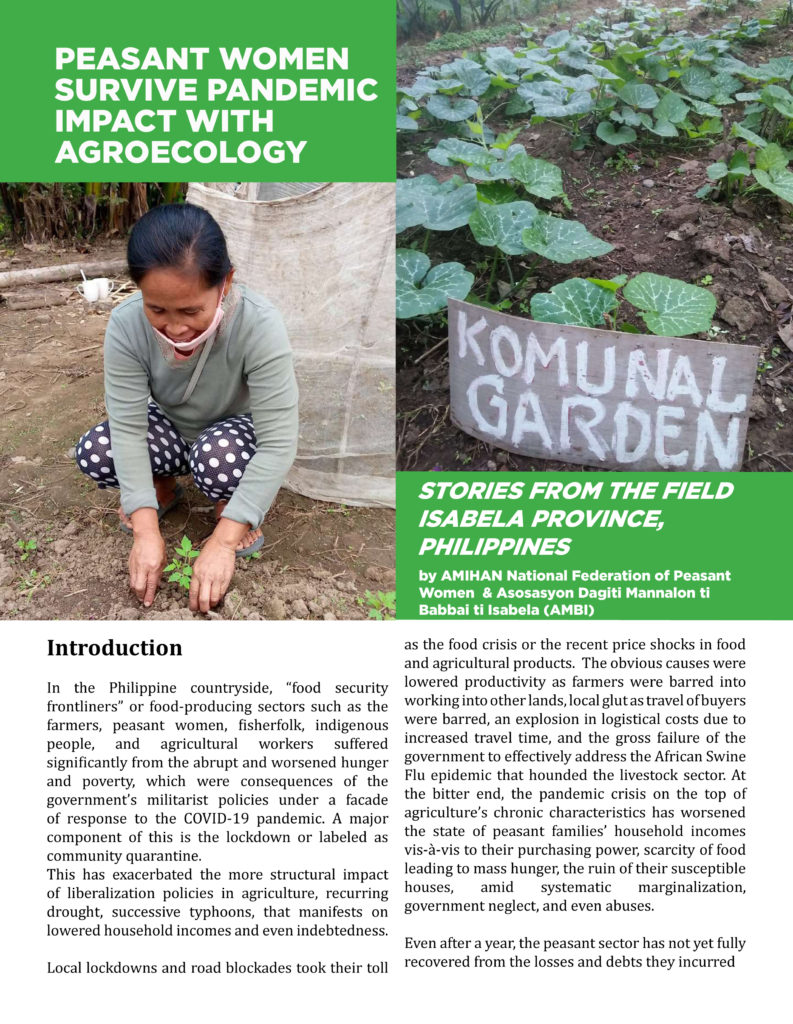

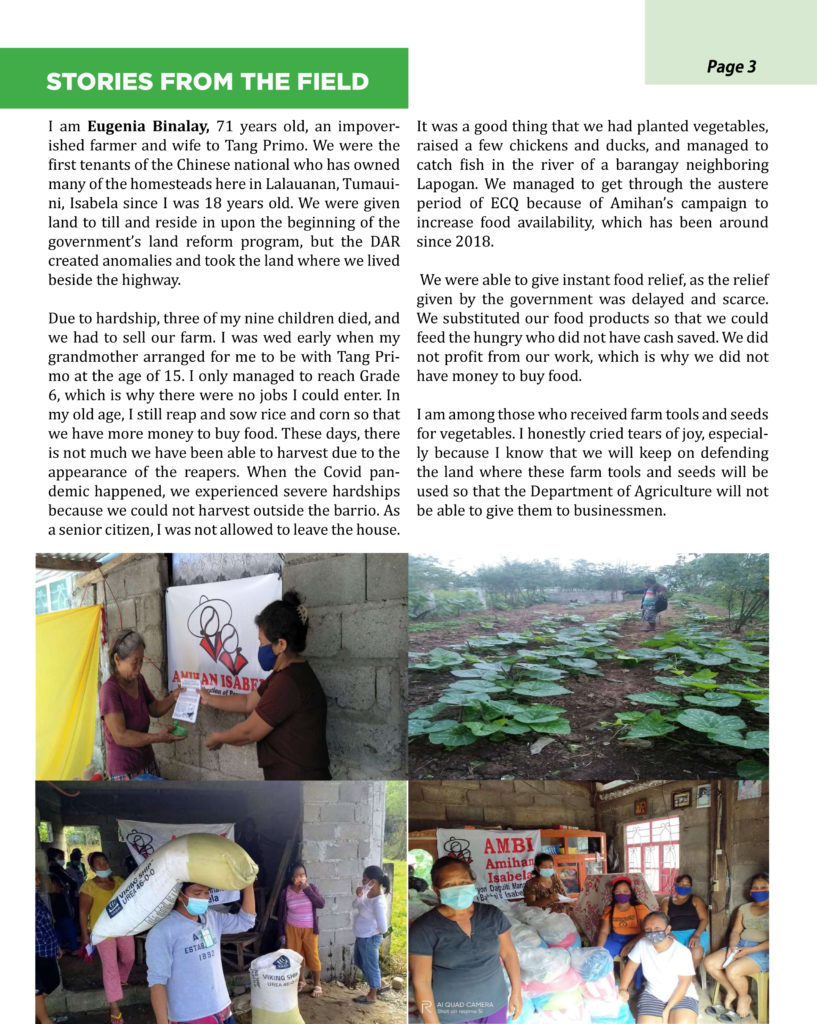

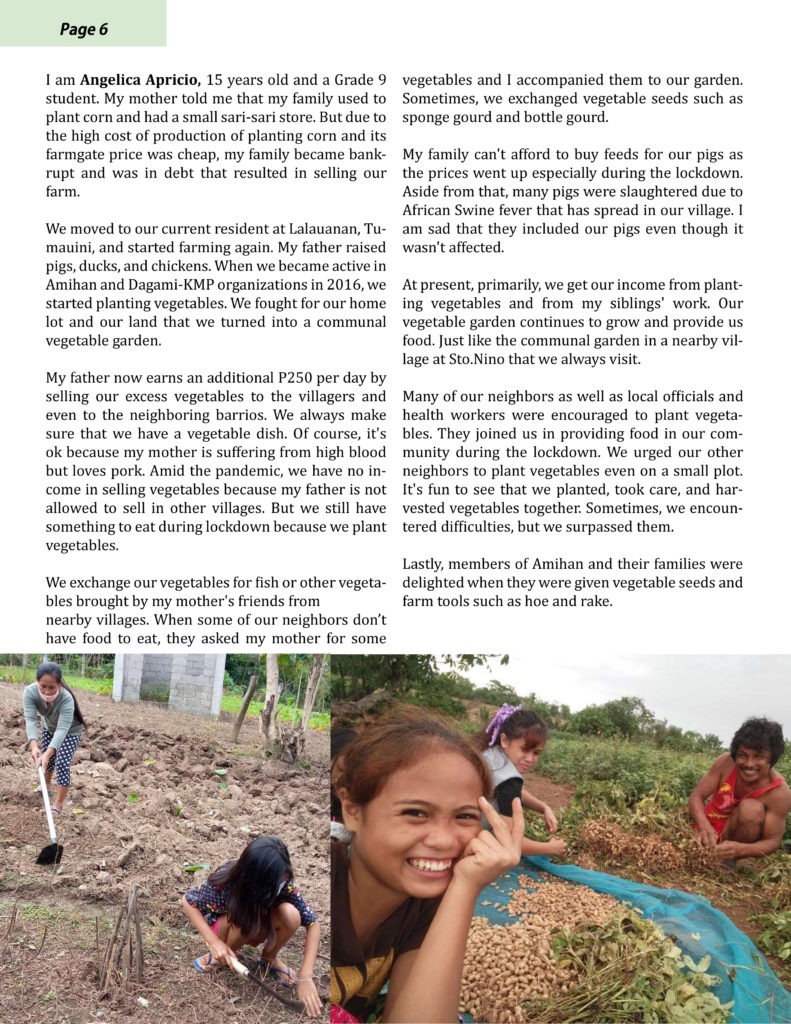

The peasant women organizations Amihan National Federation of Peasant Women and Asosasyon Dagiti Mannalon a Babbai ti Isabela or AMBI (Association of Poor Peasant Women) in Isabela province, north of the Philippines was instrumental and launched their mass campaign “Kampanya Kontra Gutom” (Campaign Against Hunger). Complementing the sustained relief drive efforts was their promotion of setting up communal vegetable farms and backyard gardens, as concrete steps for food security at the community level. As an improvement, the aid of the Agroecology Fund was key to agroecology practices, which is akin to “liberation” from the clutches of foreign monopoly agro-corporations that control seeds and their corresponding agrochemical inputs.

These breakthrough experiences of AMBI should be recognized and replicated in other parts of the country, if not the world. It is real-life people’s empowerment, the correctness of grassroots organizing, and concrete actions for food security and agroecology. The organized peasant women of Isabela hurdled and triumphed the hardships brought about by the pandemic and the inappropriate and ineffective government policies.