Short background

In December 1994, amid the overwhelming opposition of the Filipino people, the Philippine Senate ratified the country’s entry to the General Agreements on Tariffs and Trade –World Trade Organization (GATT-WTO). For nearing three decades, past and present regimes subscribed to neoliberalism, which is liberalization in the agriculture sector, in the name of “free trade” and “global competitiveness.”

As subservience to GATT-WTO, the country’s commitment to reduce tariff has resulted to free entry of all agricultural products. This simply made the local market as of foreign monopoly, to rake up super profits and promoted liberalization that facilitates plunder of surplus products from the sweat of the toiling farmers, peasant women, agri-workers, fisherfolk, indigenous people and other sectors.

The Filipino peasantry has repeatedly declared that liberalization of agriculture offered no protection to the local rice industry, of vegetables, onions, garlic, potatoes and other sub-sectors, worse, it was the vehicle for the detrimental impacts. Local farmers have grumbled and cried bankruptcy since the beginning against the flooding of imported agricultural products.

Preposterously, Philippines as an agricultural country, has become a net importer of rice. Within less than five years of the WTO regime, in 1998, rice imports flooded at 2.2 million metric tons (MT). It was twenty-fold of the then-set Minimum Access Volume (MAV) and reached to 40% of the total production.

The influx of imported rice was synonymous to severe rice crisis. Retail prices of rice speedily doubled and even tripled in the countryside. It forced millions of poor Filipinos into chronic hunger, via reduction of consumption, reaching extremely once a day. The government blamed the crisis to low productivity and its subsequent shortage. Millions of metric tons of rice from the world market at the aim to fill up the deficit.

As imported products flooded the market, local agricultural production continued to decline. Due to lack of government subsidies and high production costs, the livelihood of farmers has been put at constant risk and food security threatens the entire nation.

Who benefitted from the WTO?

The Filipino farmers, peasant women and poor sectors did not benefit from the WTO. The “free trade” banner of the WTO is obviously unequal and one-sided global trade between the small and wealthy economies. Poor sectors of third-world societies such as in the Philippines have been victims of WTO-dictated and guided policies and programs.

While foreign monopolies enjoyed their “winning positions,” raking profits, Filipino peasants and peasant women were thrown repeatedly to worsening “losing” positions. The “export-oriented and import-dependent” character of agriculture and economy has been intensified, and its chronic symptoms include displacement of jobs and livelihood of millions in agriculture and manufacturing sectors, all because of subservience to the WTO.

Some of the effects of the WTO are as follows:

- High cost of agricultural production

- Lack of support and subsidies from the government for the production of farmers

- Low prices of agricultural products

- Inflation and high prices of goods, services

- Land grabbing and speculations

Local and foreign policy in the Philippines:

- Agreement on Agriculture (AoA)

- Removal of Tariff and all non-tariff barriers

- Reduction of Domestic Subsidy

- Reduction of Export Subsidy

- Public Law 480 or the U.S. Food for Peace Program $ 20 million US loan to the Philippines for the import of rice, corn and other products according to U.S. dictation. According to the Dept. of Agricultura, is a “concessional sales program to promote exports of U.S. agriculturalcommodities. ”

- Republic Act 8178 – substituting Quantitative Import Restrictions on agricultural products, except rice, tariffs and forming the Agricultural Competetiveness Enhancement Fund (ACEF). Legislated in 1996, this law promotes seven other laws that prohibit importation or impose regulations on the importation of vegetables (onions, potatoes, garlic, cabbage and so on), coffee, livestock cattle and tobacco products.

- Rice sector liberalization in exchange for $ 175 million in loans from the Asian Development Bank, including NFA privatization, removal of rice subsidy to consumers and removal of rice import restrictions.

Duterte’s RA 11203 or Rice Liberalization Law

According to Ibon Foundation, the law removes quantitative restrictions or limits to rice importation. Imported rice from Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) countries can now be imported at 35% tariff and for rice from non-ASEAN members at 50% tariff. This complied with the WTO – Agreement on Agriculture (AoA). Under the new law, a lip-service provision, the Rice Competitiveness Enhancement Fund (RCEF) will be sourced from tariff revenues and allocates Php10 billion annually for six years supposedly to support Filipino rice farmers and local production.

Akin to the worsening experience of Filipino peasants from the increasing imports since 1995, at the very beginning of the law, its injurious impact of bankruptcy and displacement of local farmers, have been dissented and the looming expanded land-use conversion has been raised. It also failed its broken record promise of lowering the retail prices. At the very shortest time, the law exposed itself and vindicated the protesting farmers and poor consumers who are upholding food security, self-sufficiency and self-reliance.

The Filipino peasant and people’s movement has been firm that the rice crisis could only be solved via genuine agrarian reform or protected farmers’ rights to land, and a nationalist and democratic rice industry development program. These are encoined in the present legislative measure House Bill 477 Rice Industry Development Act (RIDA) and HB 239 Genuine Agrarian Reform Bill (GARB) at the lower house of the Philippine legislative branch.

RIDA proposes a P495-billion budget for the three-year rice development program, composed mainly of two parts: the P185 billion for the three-year components of the Core Program, including the P25 billion for socialized credit, P45 billion for irrigation development, P30 billion for post-harvest facilities and P50 billion for farm inputs support; and the P310-billion budget for the NFA, allocated at P103 billion annually for three years.

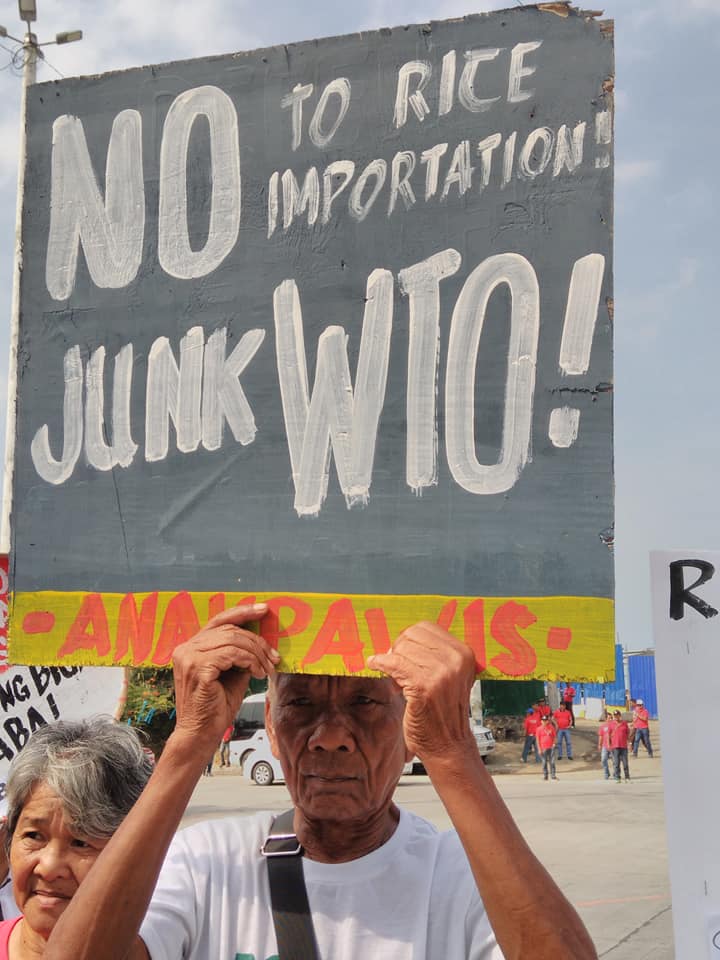

People’s Resistance vs. WTO, rice liberalization

Since the establishment of the WTO and its agreements, it has been exposed internationally as anti-people and anti-farmers. It was confronted by strong and widespread opposition and protests by the people of the world, especially workers, farmers, peasant women, fisherfolk and other sectors.

In the Philippines, under President Rodrigo Duterte’s regime, the enactment of RA 11203 or Rice Liberalization is just a band-aid solution that does not cure nor solve, but adds more holes and contributes to the worsening of the problem, that is undermining rice self-sufficiency or the productive capacity of the country to produce its own rice.

The deceptive scheme of neoliberal advocates that “more imports will mean lower prices,” has been repeatedly defunct, as obviously prices are dictated by the “free” private sector, operating as cartels, enjoying the “liberalized” sector, and they secure price levels for super profits, amid widespread hunger and misery of poor sectors.

Since the worsening symptoms of the rice crisis in 2018, the peasant, peasant women and poor consumers have been carrying out series of protests, discussions, dialogues, and even lobbying to policy-makers. Amihan or the National Federation of Peasant Women, acting as the secretariat of the rice watch group Bantay Bigas, held the “Women’s March vs. Rice Liberalization,” that coincided with the Women’s Month last March this year. In April 9, 2019, Amihan and Bantay Bigas led the Third National People’s Rice Conference (NPRC) to unite various sectors of the Filipino people and rice stakeholders against rice liberalization and for the pushing of the enactment of RIDA.

Amihan and Bantay stated that,“Instead of the country’s reliance on imported rice, the only solution is to have a comprehensive government production program and promote food security and sufficiency to solve the rice crisis within the framework of implementing Genuine Land Reform and National Industrialization. Farmers and peasant women who are the country’s leading food producers should own land and at the same time develop agricultural mechanization and provide free irrigation on farms.”